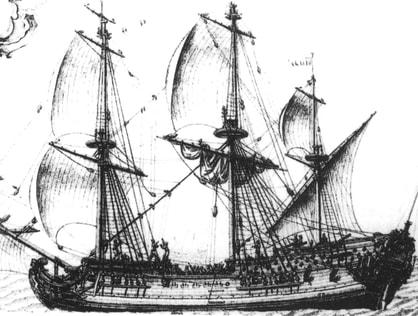

Queen Anne's Revenge, pictured to the left, is speculated to have been constructed in 1710. As a 200-ton frigate used firstly as a French merchant ship, then later as a privateer fleet in the Triangular Trade, she was appointed as Blackbeard's flagship upon her capture in 1717. In May 1718, having been Blackbeard's flagship for just under a year, she was run aground in Topsail Inlet.

After her discovery in 1996, Mark Wilde-Ramsing's archaeological research confirmed that the wreckage was in fact that of Edward Teach's flagship. The archaeological record shows that when QAR was run aground, the process was slow and allowed enough time for Blackbeard and his crew to safely evacuate and take their belongings (or, rather, Blackbeard and a few men to claim the entire loot and leave the majority of the crew with nothing).

While many of the men's more personal and valuable belongings were taken off the ship by the crew, the materials left on the ship and discovered by Mark Wilde-Ramsing provide insight to the lifestyle and every day practices of the men on the ship. Among the loaded cannons and general weaponry, a unique conglomeration of items were found that tell us about the beliefs, practices, and routines of not only the men on the ship, but of society.