Part of what makes the Bellamy Mansion’s history so unique is the trials and tribulations faced in the short time period after the mansion’s construction in 1859 and the family’s move into the mansion itself in 1861. While an integral part of the Bellamy’s history is centered around what it represents for both pre and post-Civil War life in America, it is also significant in the introspection it provides into the lives of Wilmingtonians during the Yellow Fever of 1862.

Having just moved into their Wilmington mansion in 1861, the commencement of the Civil War that same year in April brought with it not only warfare and heightened tensions between the Union and the Confederacy, but a deadly disease to one of the most essential Confederate blockade-runner bases: Wilmington. With many of these ships sailing from tropical locations, primarily Bermuda and the Bahamas (in which Yellow Fever originates and thrives) the epidemic is now known to have been brought by the ships not from their crews, but by bringing with them infected mosquitoes from tropical areas. Albeit Yellow Fever has no cure, the disease causing nausea, fever, and in extreme/late cases, fatal heart, kidney, and liver conditions, it is easily identifiable and manageable with modern medicine; though, back in 1862, the outbreak of Yellow Fever caused mass speculation and hysteria with its swiftness in claiming the lives of hundreds of Wilmingtonians. In Ellen Bellamy’s “Back with the Tide,” she reinforces the strength with which Yellow Fever ravaged Wilmington with her statement that over half the population of Wilmington fled (including the Bellamys themselves), and of the 1505 cases, 43% of them died of the fever.

Dr. William T. Wragg, a prominent practitioner from Charleston, SC, was brought into Wilmington to help identify the cause of and treat the Yellow Fever epidemic. In 1864, he wrote a report for the Confederate States Medical and Surgical Journal, titled "Report on the Yellow Fever Epidemic at Wilmington, N.C in the Autumn of 1862."

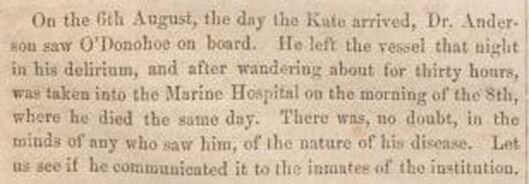

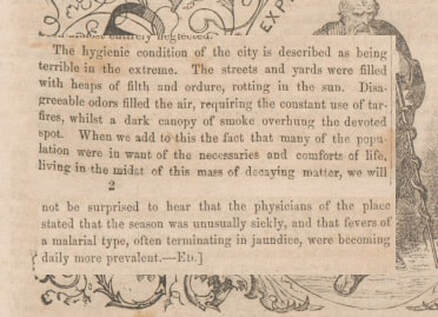

Dr. William T. Wragg, a prominent practitioner from Charleston, SC, was brought into Wilmington to help identify the cause of and treat the Yellow Fever epidemic. In 1864, he wrote a report for the Confederate States Medical and Surgical Journal, titled "Report on the Yellow Fever Epidemic at Wilmington, N.C in the Autumn of 1862." With modern medicine and technology that allows us to better understand and therefore treat Yellow Fever in today’s day and age, the lack of understanding in the 1860’s - even by the most qualified and educated doctors, like Dr. Bellamy - of the fever’s origin and the manner by which it spread caused a panic to concurrently spread with the infection. Upon identification of Yellow Fever, doctors, news writers and reporters, and the general population alike theorized how the disease found and spread through Wilmington. Between accounts of the infection in newspapers and the opinions of doctors and physicians, like that of Dr. William T. Wragg in the excerpt to the left and below, multiple theories surrounding the root and continued persistence of the disease developed.

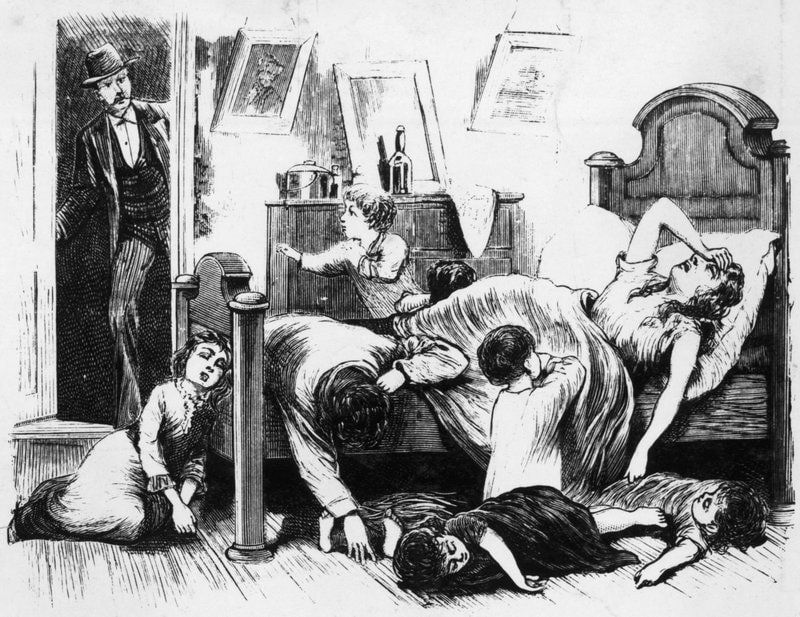

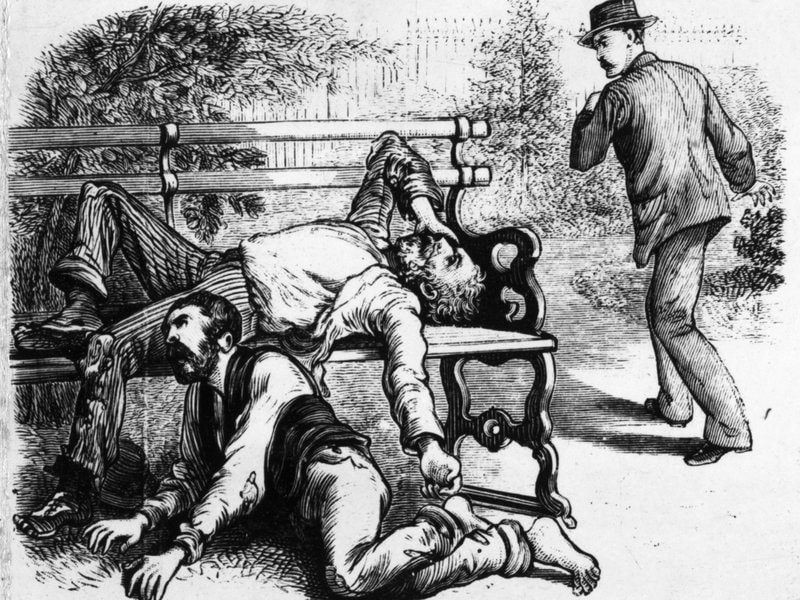

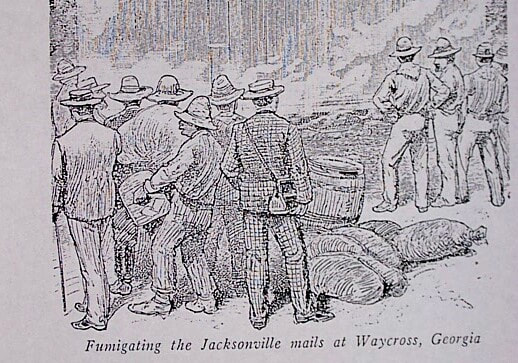

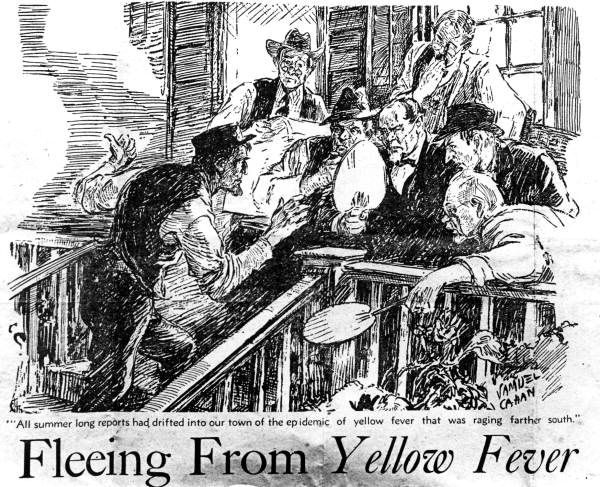

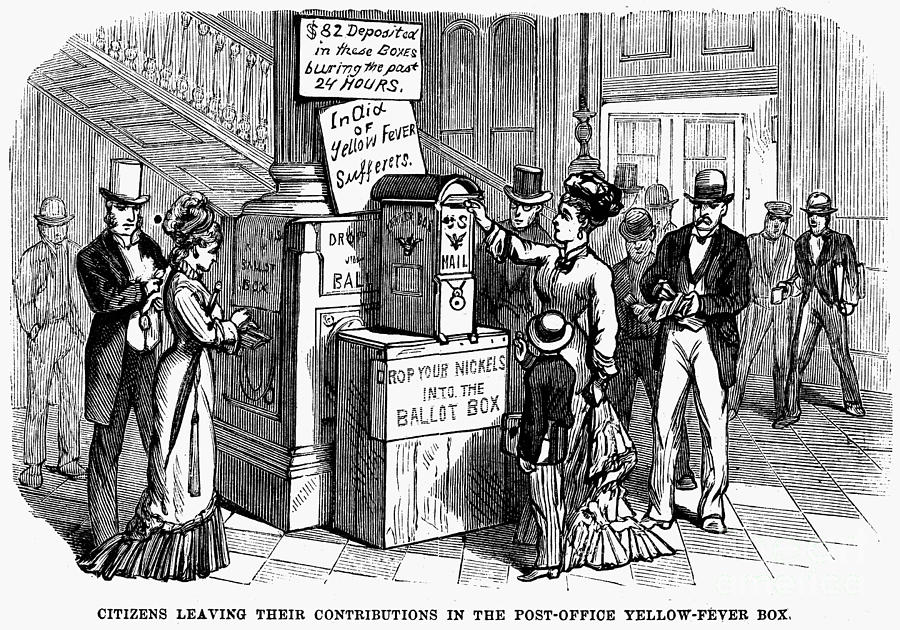

At this time, across much of the Union and Confederacy, newspapers functioned as a primary source of communication and information; in reporting updates on Yellow Fever, this was no exception. News articles reported fervently on the epidemic, recounting the lives it affected and claimed through both imagery and articles giving advice on how to avoid and treat the disease. Despite the media's constant reassurance that there be no need for panic, many newspapers inserted illustrations of the disease that provided shock value and further perpetuated the hysteria surrounding the spread of the infection. Below are some of the depictions found throughout newspaper articles depicting Yellow Fever.

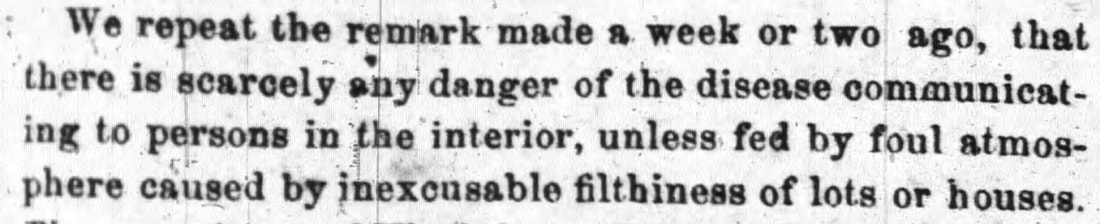

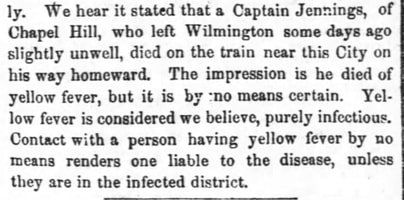

Raleigh’s Semi-Weekly Standard speculates that the city of Wilmington itself is infectious, and the risk of being infected only occurs upon direct contact with the city – not its citizens.

Raleigh’s Semi-Weekly Standard speculates that the city of Wilmington itself is infectious, and the risk of being infected only occurs upon direct contact with the city – not its citizens. Through the speculation of doctors, physicians, and the public, the general consensus seemed to be that the poor sanitation of the city and intermingling with the sick were the primary proponents in the spread of the infection. In response, many families fled Wilmington to surrounding, uninfected counties. The families who had the capability to flee – like the Bellamys – were extremely fortunate; those who remained in the city by the end of the fall of 1862 essentially belonged to three categories: soldiers commanded to remain stationed there, slaves (for example, Sarah, a Bellamy slave, who was appointed to maintain the mansion in the family’s absence), and the sick who were unable to leave.

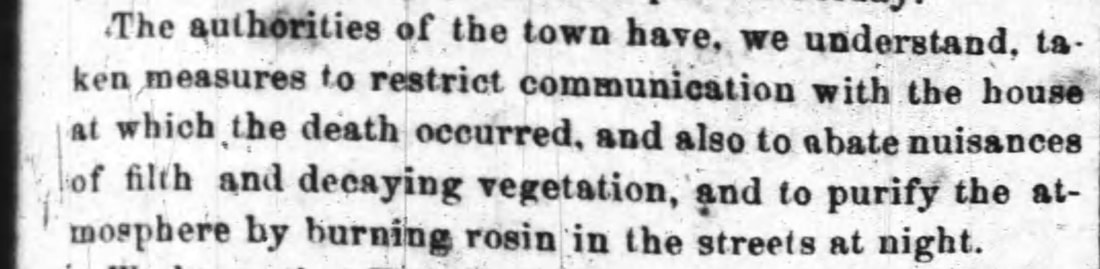

Speculation on the origin and spread of the disease didn’t cease in Wilmington, however. Newspapers from surrounding counties, like the Fayetteville Semi-Weekly Observer or Raleigh’s Semi-Weekly Standard, also weighed in on issues concerning the epidemic.

Speculation on the origin and spread of the disease didn’t cease in Wilmington, however. Newspapers from surrounding counties, like the Fayetteville Semi-Weekly Observer or Raleigh’s Semi-Weekly Standard, also weighed in on issues concerning the epidemic.

The Fayetteville Semi-Weekly Observer proposes the sanitation of Wilmington – like many speculated at the time – to be one of the driving factors behind the epidemic’s rampage through the city.

Looking back through the first-hand accounts of Wilmingtonians, like Ellen Bellamy, to the outside perspectives of neighboring county’s newspaper reporters, we’re able to follow not only the disease in terms of the infection itself, but the simultaneous spread of somewhat of a hysteria. We’re able to look back on these 19th century newspaper articles and medical journals and see how these theories manifested themselves in helping shape our modern understanding of Yellow Fever, and how clouded understanding of the disease affected the city that the Bellamy’s had just come to call home.

To learn more about the theories following the epidemic at the time, who it affected, and its immediate and lasting impact on Wilmington, attend our free lecture by Dr. Kimberly Sherman on Thursday, January 30th at 6:00 PM. Though it is free, there is limited seating – so doors open at 6 PM!

To learn more about the theories following the epidemic at the time, who it affected, and its immediate and lasting impact on Wilmington, attend our free lecture by Dr. Kimberly Sherman on Thursday, January 30th at 6:00 PM. Though it is free, there is limited seating – so doors open at 6 PM!

Written by UNCW Anthropology student and Bellamy Intern, Payton Schoenleber.