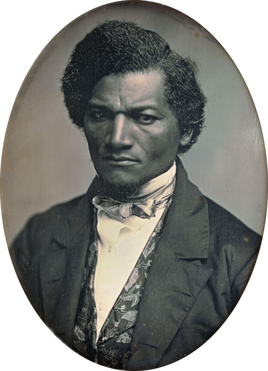

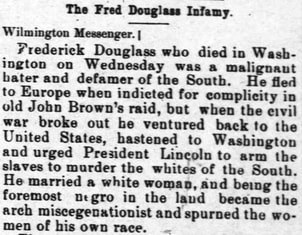

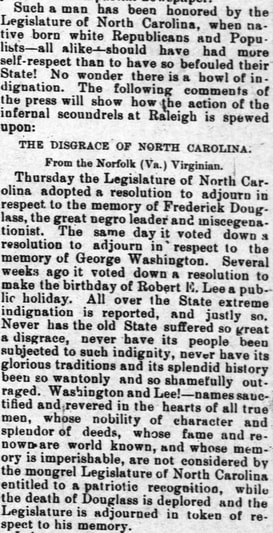

| As a leading activist in the effort to end slavery, while Frederick Douglass was harrowed as a hero and treated (relatively) as an equal in the Union, the South, rather, viewed him as undeserving of not only the title of hero, but of recognition at the expense of Confederate soldiers. Being a former slave, they questioned and invalidated his qualification both during his life, as a leader in the abolition movement, and in his death, to be recognized before Confederate heroes, like Robert E. Lee and George Washington, mentioned in the excerpt from the Fayetteville Observer to the left. How can a man be so equally loved and hated? In developing an understanding for the divide that existed between the Union and Confederacy, in regard to ways of life and opinions on Frederick Douglass himself, we can start by looking into Douglass' journey from boyhood to manhood, uneducated child to young author, voiceless slave to social reformer and orator. |

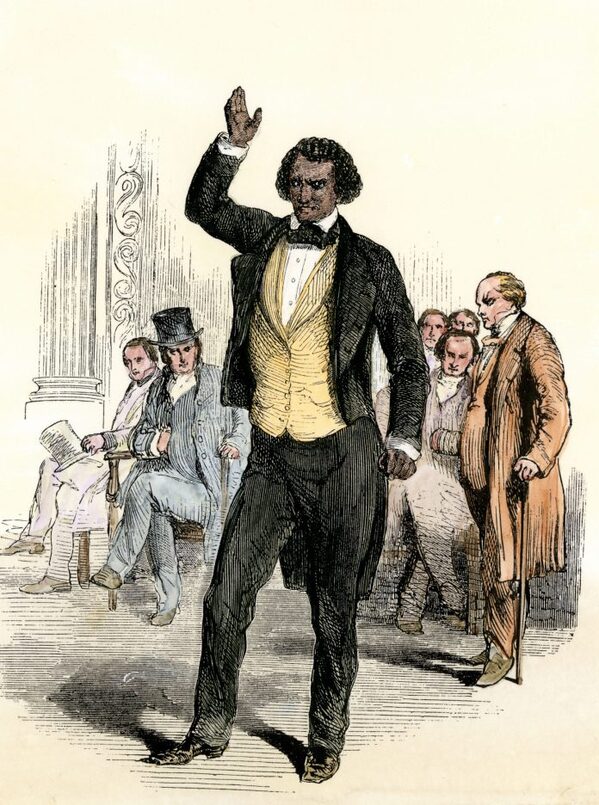

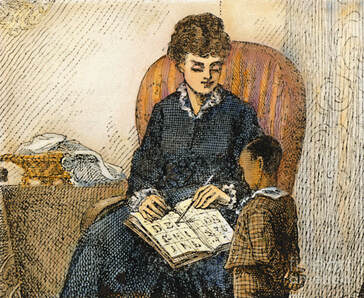

An illustration of Lucretia Auld, slavemaster Thomas Auld's wife, teaching a young Frederick Douglass the alphabet.

An illustration of Lucretia Auld, slavemaster Thomas Auld's wife, teaching a young Frederick Douglass the alphabet. Douglass's passion for knowledge didn't stop after his youth; years later, Douglass began hosting private Sunday school classes for fellow slaves, marking the beginning of his philanthropic work. The hosting of these classes was pivotal in marking a transition from a self-propelled desire for knowledge, to his developing a passion to educate and liberate others. Douglass's private Sunday meetings went relatively unnoticed for a six-month period before they were found out by their slave-owners and Douglass was subsequently sent to Edward Covey, or rather, the "slave breaker."

The irony behind Covey's title as the "slave breaker" can be found in the first sentence of Douglass's autobiography, stating: "You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man." Covey broke not the slave, but the slavehood, of Douglass. Five years after his relocation from the plantation in which he hosted his Sunday schools, at the age of 20, Douglass became a free man by a journey that took him less than 24 hours to complete. Resettling in an abolitionist hub in Massachusetts, Douglass attended and later led segregation protests, joined abolitionist organizations, became a licensed preacher, and cultivated his oratory skills that led him to become one of the greatest speakers of his, and arguably of all, time.

Douglass went on to travel abroad, write five autobiographies (and countless other important works), fight for emancipation and suffrage, deliver the Emancipation Memorial speech, serve as president and chairman of newspapers and governmental positions before dying of a heart attack at home at the age of 77. Through following his journey from slavery to freedom, we concurrently watch the journey of a young boys' hunger for and acquisition of knowledge, grow into the desire to share his wealth. Douglass' humble beginnings in contrast to the accomplishments he had accumulated by the time of his death in 1895 were what painted him to some, a seasoned hero, and to others, an unqualified villain.

Frederick Douglass. (2018, February 2). Retrieved February 11, 2020, from https://www.nps.gov/frdo/learn/historyculture/frederickdouglass.htm

Frederick Douglass timeline. (1818, February 1). Retrieved February 13, 2020, from https://www.timetoast.com/timelines/frederick-douglass-a771bcbb-062b-4973-885d-922195f0962d

Mrs. Auld Teaching Frederick Douglass to Read. (Hartford Conn. Publishing Co., 1881.). Retrieved from https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglasslife/ill4.html

The Frederick Douglass Infamy. (1895, February 28). Fayetteville Weekly Observer. Retrieved from http://newspapers.com