Works Cited:

Bishir, Catherine W. The Bellamy Mansion. Raleigh, Historic Preservation Foundation of North Carolina, 2004. Print.

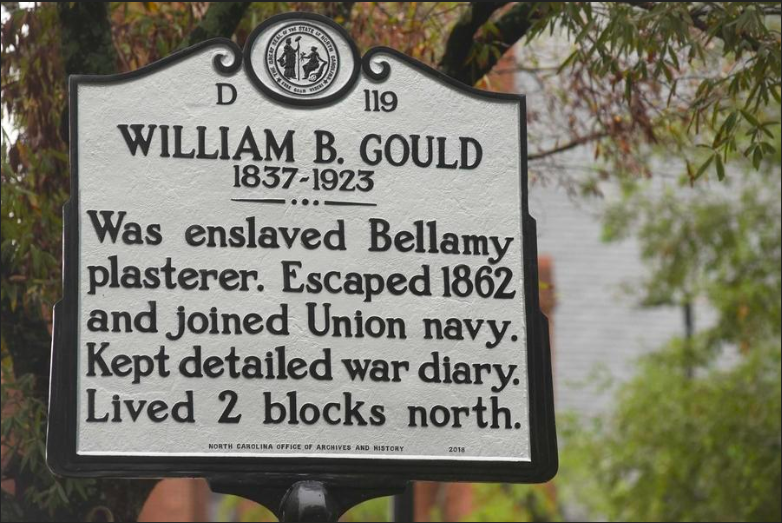

——. “Gould, William B. I (1837-1923).” North Carolina Architects and Builders, NCSU Libraries, 2015. Web. Accessed 19 Nov 2018. http://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/people/P000320.

“Criteria for Historic Markers” and “Placement …” ncmarkers.com, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 2008. Web. Accessed 19 Nov 2018. http://www.ncmarkers.com/Home.aspx

“Gould IV to lecture on Civil War ancestor.” starnewsonline.com, GateHouse Media, 23 Oct 2018. Web. Accessed 19 Nov 2018. https://www.starnewsonline.com/news/20181023/gould-

Iv-to-lecture-on-civil-war-ancestor.