by Beth Mentesana

Thanksgiving festivals have been celebrated since the 1600s, initially to give thanks for the blessings of a bountiful harvest or drought-breaking rain. They didn’t become an annual event until the 1700s, when each state set aside a different day for the holiday. And it was not until November 26, 1789 that a national celebration of Thanksgiving was proclaimed by President George Washington.

Thanksgiving festivals have been celebrated since the 1600s, initially to give thanks for the blessings of a bountiful harvest or drought-breaking rain. They didn’t become an annual event until the 1700s, when each state set aside a different day for the holiday. And it was not until November 26, 1789 that a national celebration of Thanksgiving was proclaimed by President George Washington.

| It’s hard to imagine this in today’s world, but our country had few common holidays back then: civic, cultural or religious. Aside from Independence Day (July 4) and Washington’s Birthday (February 22), there were no civic holidays universally regarded or celebrated among Americans, according to historian Charles LeCount from the Genesee Country Village & Museum near Rochester, NY. And arguably these days were not celebrated by the country’s many enslaved African Americans or its Indian inhabitants. |

America in the early 19th century was a country with little history and virtually no shared customs, says LeCount. Divisions were everywhere. Americans saw themselves first as a Virginian or a New Yorker, or as a New Englander, Westerner or Southerner before they considered themselves American. The country was full of immigrants from Ireland, Germany and England.

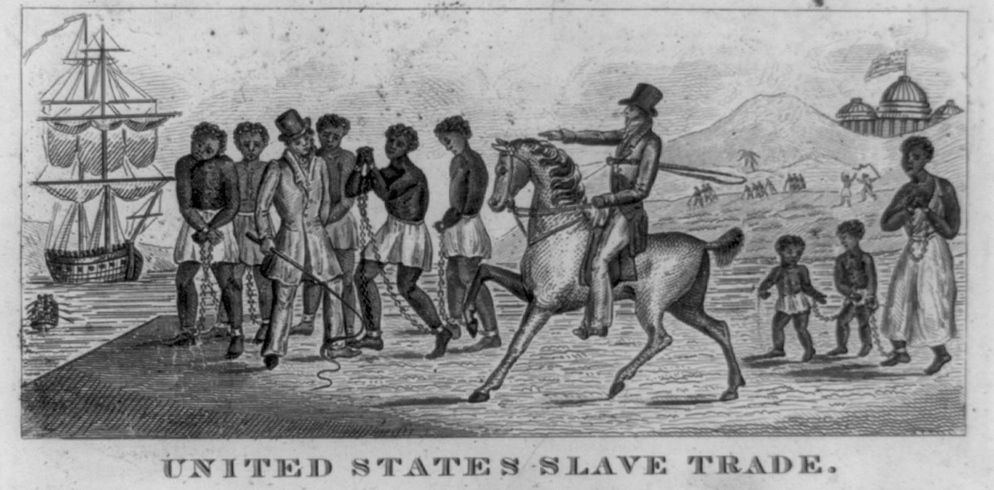

The country was also full of slaves from Africa – four million of them in the South alone. The practice of importing slaves from Africa to North America was abolished on January 1, 1808, although it continued illegally for many years after that. The widespread trade of slaves within the South was not prohibited, however, and children of slaves automatically became slave themselves, thus ensuring a self-sustaining slave population in the South. In northern cities like New York, Philadelphia and Boston, January 1 was commemorated by the black community as a day of thanksgiving and gratitude for the next 20 years or so.

The country was also full of slaves from Africa – four million of them in the South alone. The practice of importing slaves from Africa to North America was abolished on January 1, 1808, although it continued illegally for many years after that. The widespread trade of slaves within the South was not prohibited, however, and children of slaves automatically became slave themselves, thus ensuring a self-sustaining slave population in the South. In northern cities like New York, Philadelphia and Boston, January 1 was commemorated by the black community as a day of thanksgiving and gratitude for the next 20 years or so.

Texas was the first Southern state to declare Thanksgiving a holiday in 1848 followed by North Carolina in 1849 when Governor Charles Manly set the date for November 15.

Individual Southern families, especially those with Yankee relatives, enjoyed Thanksgiving, but as a holiday it still lacked widespread observance below the Mason-Dixon line, writes Dr. Libby O’Connell, chief historian for the History Channel. For one thing, it was totally eclipsed by Christmas, a holiday increasingly popular in the 19th century. Moreover, she says, some Southern leaders saw Thanksgiving as a Yankee holiday laced with overtones of abolitionism, due in part to the Northern practice of giving public speeches on that day, some of which referenced the evils of slavery.

An 1858 entry in the diary of Bellamy Mansion assistant architect Rufus Bunnell gives us some insight on how the holiday was observed (or not) in antebellum Wilmington. First, he writes “the Great Christmas holiday of the Southern States in slavery times was celebrated in as noisy and as lively a manner as a northern Fourth of July.”

Then, on November 24 of that year he tells us “there was some variety in the spending of that North Carolina thanksgiving day.” In the morning he did some sketches for the Wilmington & Weldon railroad depot, he remarked that the weather was a little too cool for sitting in the shade but too warm in the sunshine, and after dinner drank some eggnog with a friend. While he visited with a few of his southern friends, Bunnell notes that the day’s celebrations were more “pleasant and homelike” with his northern friends.

Neither Ellen Bellamy nor her brother John Jr. makes a single reference to a Thanksgiving celebration in their memoirs. The Christmas feast at Uncle Taylor’s house, on the other hand, merits its own “chapter” in Ellen’s book. Which is not to say that the family didn’t observe the holiday in some way or another. We know they raised turkeys in town and on the plantation at Grovely. Ellen describes the “chicken and turkey house” behind the Market Street home as “a neat little structure, slatted in front and side, tin roofed, was built in yard this end of stable.” And John Jr. references the “turkey, peafowl and chicken yards” near the manor house at Grovely.

When the Civil War broke out in the spring of 1861, the observance of holidays was not uppermost in the mind of any American. However, Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America, declared Friday, the 15th day of November 1861 as a “Day of Fasting & Humiliation (not Thanksgiving!)” and less than a year later, again declared a different day -- Thursday, the 18th day of September -- as “a day of prayer and thanksgiving to Almighty God for the great mercies vouchsafed to our people, and more especially for the triumph of our arms at Richmond and Manassas.”

Individual Southern families, especially those with Yankee relatives, enjoyed Thanksgiving, but as a holiday it still lacked widespread observance below the Mason-Dixon line, writes Dr. Libby O’Connell, chief historian for the History Channel. For one thing, it was totally eclipsed by Christmas, a holiday increasingly popular in the 19th century. Moreover, she says, some Southern leaders saw Thanksgiving as a Yankee holiday laced with overtones of abolitionism, due in part to the Northern practice of giving public speeches on that day, some of which referenced the evils of slavery.

An 1858 entry in the diary of Bellamy Mansion assistant architect Rufus Bunnell gives us some insight on how the holiday was observed (or not) in antebellum Wilmington. First, he writes “the Great Christmas holiday of the Southern States in slavery times was celebrated in as noisy and as lively a manner as a northern Fourth of July.”

Then, on November 24 of that year he tells us “there was some variety in the spending of that North Carolina thanksgiving day.” In the morning he did some sketches for the Wilmington & Weldon railroad depot, he remarked that the weather was a little too cool for sitting in the shade but too warm in the sunshine, and after dinner drank some eggnog with a friend. While he visited with a few of his southern friends, Bunnell notes that the day’s celebrations were more “pleasant and homelike” with his northern friends.

Neither Ellen Bellamy nor her brother John Jr. makes a single reference to a Thanksgiving celebration in their memoirs. The Christmas feast at Uncle Taylor’s house, on the other hand, merits its own “chapter” in Ellen’s book. Which is not to say that the family didn’t observe the holiday in some way or another. We know they raised turkeys in town and on the plantation at Grovely. Ellen describes the “chicken and turkey house” behind the Market Street home as “a neat little structure, slatted in front and side, tin roofed, was built in yard this end of stable.” And John Jr. references the “turkey, peafowl and chicken yards” near the manor house at Grovely.

When the Civil War broke out in the spring of 1861, the observance of holidays was not uppermost in the mind of any American. However, Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America, declared Friday, the 15th day of November 1861 as a “Day of Fasting & Humiliation (not Thanksgiving!)” and less than a year later, again declared a different day -- Thursday, the 18th day of September -- as “a day of prayer and thanksgiving to Almighty God for the great mercies vouchsafed to our people, and more especially for the triumph of our arms at Richmond and Manassas.”

| In the midst of all of this, a woman named Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of the widely read Godey’s Lady’s Book and the equivalent of today’s Martha Stewart, had started a mission as far back as 1846 to combine all of the states' harvest festivals under one national umbrella. Her advocacy for a nationally recognized Thanksgiving holiday included magazine articles as well as written appeals to six Presidents: Taylor, Fillmore, Pierce, Buchanan and Lincoln. Her crusade lasted 17 years until it was successful, when President Lincoln set aside the last Thursday in November for the day of thanks. That was just two months after the Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. By the 1870s, all states celebrated Thanksgiving on the same day. It took another 80 years (in 1941) for our Congress to pass federal legislation agreeing on the fourth Thursday in November as Thanksgiving Day. Some things never change. |