When people tour the Bellamy Mansion, one of the first things they notice when they enter the house is the elaborate plaster moldings in the more public parts of the house. The house, designed with Greek Revival and Italianate styling, was the product of the hard work and labor of both enslaved skilled carpenters, and local, freed black artisans.

The skilled and unskilled enslaved workers in Wilmington were hired out and whatever wages they earned were given directly back to their masters. Unfortunately, we do not know the names of all of the black artisans who worked on the house. We do, however, know a great deal about one of these men thanks to his journal and the extensive work of his great-grandson, William B.

Gould IV.

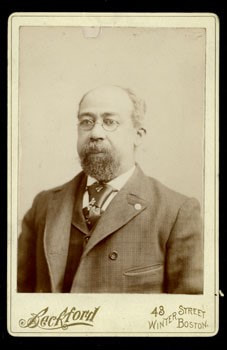

William B. Gould was born November 18th, 1837, to an English man and a slave woman in Wilmington, North Carolina. He was owned by Nicholas Nixon, who was a successful peanut planter and prominent member of the Wilmington Community. Around 1859, Gould began his work as plasterer and mason under the employment of Dr. John D. Bellamy for the construction of the Bellamy Mansion. Alongside other slaves and freeman, Gould created beautiful works of art within the molding of the house.

It was common practice for those who hired out slaves to clothe, feed, and shelter them for their duration of their work. So, it is more than likely that Gould resided in the slave quarters during his time at the Bellamy Mansion. As a credit to his hard work, Gould signed his name into the plaster of the house; forever cementing his place in the Bellamy Mansion’s history (pictured above). This is incredibly significant, because following a series of laws passed in 1830 it was declared illegal to teach slaves how to read or write in the state of North Carolina. It is probable that Gould learned how to read through the church. Nixon was Episcopal and they were notorious for looking the other way when it came to slave literacy. Peter Hinks writes, "perhaps the most common avenue to literacy for blacks was instruction by a white person who considered it their religious duty to teach their slaves how to read Scripture (2). Christopher Hager supports this claim, saying, "many slaveholders wished to make exceptions [to slave literacy laws] for religious instruction (usually by white preachers)" (114).

On September 21st, 1862, Gould, and seven other men, escaped off of Orange Street and into the Cape Fear River. Six days later they were picked up by The USS Cambridge and recorded as “contraband of war.” Gould began his three-year journal on September 27th, 1862, following his daily life in the United States Navy. After the Civil war he settled in Dedham, Massachusetts with his wife, Cornelia Read, and had eight children, six boys and two girls. He joined the Grand Army of the Republic in 1882 and held almost every position possible including the highest position, Commander. William B Gould IV, Gould’s great-grandson, wrote a book that includes Gould’s journals called Diary of a Contraband: The Civil War Passage of a Black Sailor. In this book he writes about the history surrounding his great-grandfather’s life and discusses the chronology of Gould’s diary.

Gould IV, William B. Diary of a Contraband: The Civil War Passage of a Black Sailor. Standford University Press, 2002.

Hager, Christopher. Word by Word: Emancipation and the Act of Writing. Harvard University Press, 2013. ProQuest Ebook Central,

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uncw/detail.action?docID+3301209.

Hinks, Peter P. To awaken my afflicted brethren: David Walker and the problem of antebellum slave resistance. Penn State Press, 2010.

Written by Bellamy Intern and UNCW English major Moriah Yancey

The skilled and unskilled enslaved workers in Wilmington were hired out and whatever wages they earned were given directly back to their masters. Unfortunately, we do not know the names of all of the black artisans who worked on the house. We do, however, know a great deal about one of these men thanks to his journal and the extensive work of his great-grandson, William B.

Gould IV.

William B. Gould was born November 18th, 1837, to an English man and a slave woman in Wilmington, North Carolina. He was owned by Nicholas Nixon, who was a successful peanut planter and prominent member of the Wilmington Community. Around 1859, Gould began his work as plasterer and mason under the employment of Dr. John D. Bellamy for the construction of the Bellamy Mansion. Alongside other slaves and freeman, Gould created beautiful works of art within the molding of the house.

It was common practice for those who hired out slaves to clothe, feed, and shelter them for their duration of their work. So, it is more than likely that Gould resided in the slave quarters during his time at the Bellamy Mansion. As a credit to his hard work, Gould signed his name into the plaster of the house; forever cementing his place in the Bellamy Mansion’s history (pictured above). This is incredibly significant, because following a series of laws passed in 1830 it was declared illegal to teach slaves how to read or write in the state of North Carolina. It is probable that Gould learned how to read through the church. Nixon was Episcopal and they were notorious for looking the other way when it came to slave literacy. Peter Hinks writes, "perhaps the most common avenue to literacy for blacks was instruction by a white person who considered it their religious duty to teach their slaves how to read Scripture (2). Christopher Hager supports this claim, saying, "many slaveholders wished to make exceptions [to slave literacy laws] for religious instruction (usually by white preachers)" (114).

On September 21st, 1862, Gould, and seven other men, escaped off of Orange Street and into the Cape Fear River. Six days later they were picked up by The USS Cambridge and recorded as “contraband of war.” Gould began his three-year journal on September 27th, 1862, following his daily life in the United States Navy. After the Civil war he settled in Dedham, Massachusetts with his wife, Cornelia Read, and had eight children, six boys and two girls. He joined the Grand Army of the Republic in 1882 and held almost every position possible including the highest position, Commander. William B Gould IV, Gould’s great-grandson, wrote a book that includes Gould’s journals called Diary of a Contraband: The Civil War Passage of a Black Sailor. In this book he writes about the history surrounding his great-grandfather’s life and discusses the chronology of Gould’s diary.

Gould IV, William B. Diary of a Contraband: The Civil War Passage of a Black Sailor. Standford University Press, 2002.

Hager, Christopher. Word by Word: Emancipation and the Act of Writing. Harvard University Press, 2013. ProQuest Ebook Central,

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uncw/detail.action?docID+3301209.

Hinks, Peter P. To awaken my afflicted brethren: David Walker and the problem of antebellum slave resistance. Penn State Press, 2010.

Written by Bellamy Intern and UNCW English major Moriah Yancey