Johnson was caught between the two sides that had appeared due to the war--the union supporters and the Secessionists. He himself was a Democrat from Tennessee, and in his government positions, “generally adhered to the dominant Democratic views favoring lower tariffs and opposing antislavery agitation” (“Andrew Johnson”). Yet, after Lincon’s election in 1860, Johnson broke away from the Democratic party when he voiced his dissent against Southern secession. When Lincoln eventually selected Johnson to run as his Vice President in 1864, it was merely to gain the support of “loyal ‘war’ Democrats” (“Andrew Johnson”). No one thought that he would be anything other than Vice President of the United States.

But then Lincoln was assassinated, and suddenly Johnson found himself president of a divided nation that needed to rebuild itself, with a Congress intent on doing what it determined was best for reconstruction, no matter what the new president thought. However, there was one power that President Johnson had, which he used as an attempt to pull the country back together: presidential pardons. These pardons were an attempt to bring the secessionists back into the Union, while also appeasing the Republicans who called for even harsher punishment. Johnson’s pardon gave clemency to many white Southerners, excepting those who fell under one of the fourteen exceptions listed in his Amnesty Proclamation decreed on May 29th, 1865. In addition, the pardon restored all property (except former slaves) and rights of a US Citizen to the former Confederates.

As for the pardon process itself, it involved a number of steps before an individual could obtain one. Johnson first “pardoned all who would take an oath of allegiance, but required leaders and men of wealth to obtain special Presidential pardons” (“Andrew Johson” whitehouse.gov). These leaders and men of wealth had to make a trip to Washington D.C. or send a representative in their stead. However, it is possible that these individuals were more successful if they appeared themselves to request a personal pardon from President Johnson (“Restoring the Union”). These men were additionally required to also swear an oath of allegiance to the Union and promise to uphold the 13th amendment which abolished slavery.

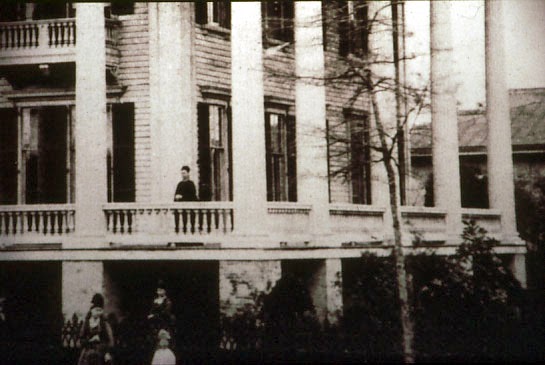

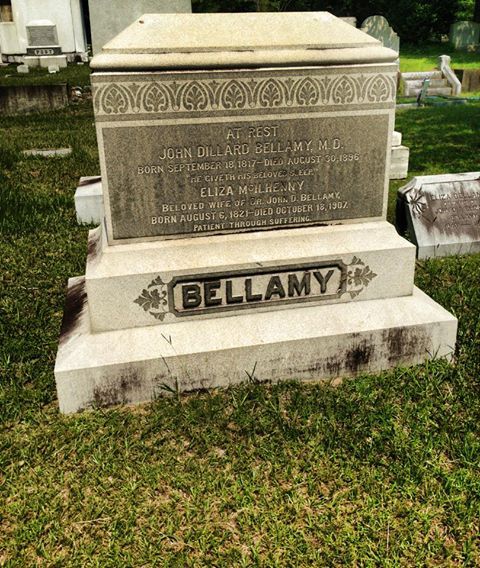

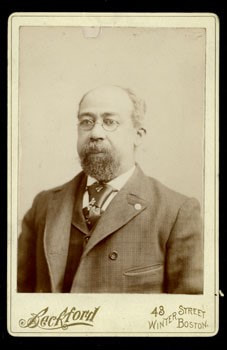

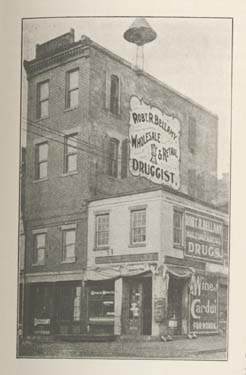

While we don’t know everything about John D. Bellamy’s pardon process, the aforementioned steps to obtain a pardon are likely the same that Dr. Bellamy had to go through himself. As Dr. Bellamy fell under the 13th exception to President Johnson’s Amnesty proclamation, that “All persons who have voluntarily participated in said rebellion, and the estimated value of whoso taxable property is over twenty thousand dollars” (“President Johnson's Amnesty Proclamation”), he was an individual who had to receive a personal pardon. We know from records that he began the process of obtaining his pardon in July 1865 and continued into August and early September when he finally received it. Dr. Bellamy and his family did not move back into their home until late September or early October of 1865. It would not be improper to surmise that he was traveling back from getting his pardon during the gap in events. Else, if he had sent a representative to get his paperwork in order, this time would account for the paperwork being sent to Dr. Bellamy. Despite the fact that this time period is murky in that the exact events and processes that transpired were not recorded, we know for sure that Dr. Bellamy did indeed receive his pardon from the president and was able to finally settle back into the home that he had built for his family five years earlier.

Works Cited:

- "Andrew Johnson.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 12 Oct. 2018, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Johnson.

- “Andrew Johnson.” The White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/andrew-johnson/

- Foner, Eric. “Reconstruction.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 5 Jan. 2018, https://www.britannica.com/event/Reconstruction-United-States-history#ref226039.

- Kochan, Donald J. “B. The Confiscation Act of 1862 and Civil War Forfeitures.” Mackinac Center for Public Policy, 1 July 1998, https://www.mackinac.org/1278.

- “President Johnson's Amnesty Proclamation.; Restoration to Rights of Property Except in Slaves. An Oath of Loyalty as a Condition Precedent. Legality of Confiscation Proceedings Recognized. Exception of Certain Offenders from this Amnesty. By These Special Applications for Pardon May be Made. Reorganization in North Carolina. Appointment of a Provisional Governor. A State Covention to be Chosen by Loyal Citizens. The Machinery of the Federal Government to be Putin Operation. AMNESTY PROCLAMATION.” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/1865/05/30/archives/president-johnsons-amnesty-proclamation-restoration-to-rights-of.html.

- “Restoring the Union.” Lumen Learning (OER Services), https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-ushistory2os2xmaster/chapter/restoring-the-union/.